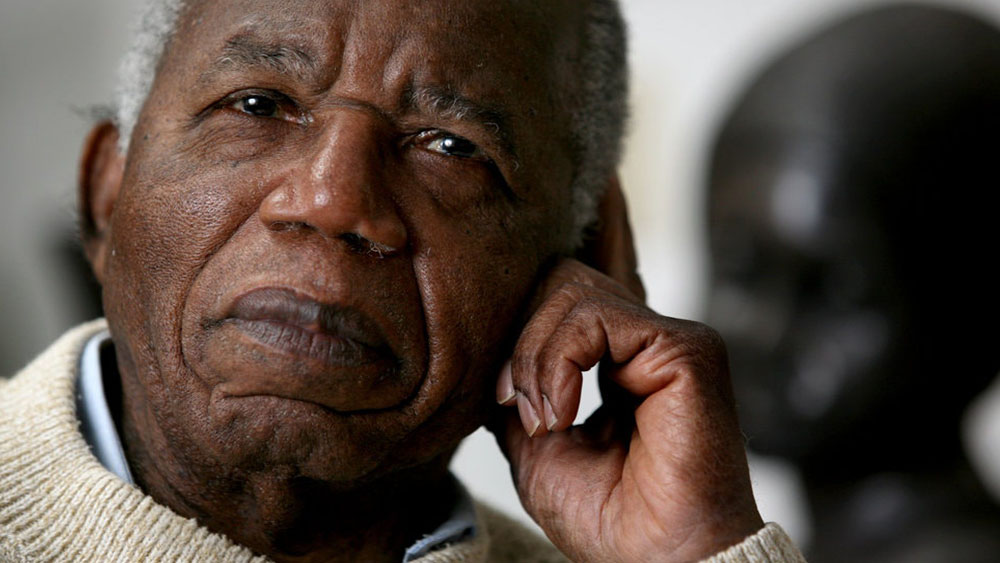

In 1983, the Nigerian novelist, Chinua Achebe, received a peculiarly unusual letter. One of his former students at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, had written to him, “asking timidly for permission to write his biography.” Achebe wouldn’t respond to the request because he kept forgetting, and whenever it flashed through his mind he would “either be in a plane or in a foreign country.”

Persistent, the student went to Nsukka the following year where he met Achebe. The globally revered author invited him to his office, and right there verbally consented to the biographical work, “although he [Achebe] made it clear that he would not be involved.” But oral consent wasn’t enough for the young man; he wanted a clearly written endorsement letter. The letter would come in 1985 and it was gracefully succinct:

Ezenwa-Ohaeto who was my student and is now a lecturer has informed me of his desire to write my biography. I have no doubt that he will bring to both research and writing a sense of seriousness. I have therefore given my general approval to his project.

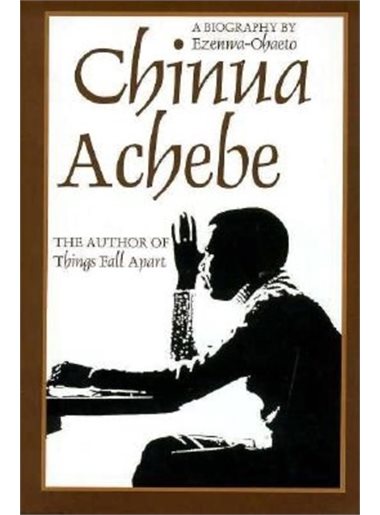

Ezenwa-Ohaeto, for that was the name of Achebe’s former student, admitted that although he had not thought writing the story of a towering figure would be a tea party affair, Achebe’s comment on seriousness “had a sobering effect.” Ezenwa-Ohaeto knew he had to be careful in fishing for details from sources and “in digging out the facts.” The biography, published more than a decade later, would be titled, Chinua Achebe: A Biography, and would go on to win the Choice Outstanding Book Award for 1998. The novelist, Chukwuemeka Ike, told me that Ezenwa-Ohaeto was “a serious minded scholar” and the critic Professor Chimalum Nwankwo described the book as a “classic”.

Tall and huge, “a hugeness which came with age,” was how Ezenwa-Ohaeto’s widow, Ngozi, now an Associate Professor in the department of English at Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, described her husband during our interview. In her early fifties, she was on low haircut, her thoughtful face barely made up and bespectacled. The interview took place in her office at noon, her desk heavy with books, some of which were co-authored by her, others revolving round her husband’s unpublished essays. Achebe’s biography was remarkably visible on the table.

What was Ezenwa-Ohaeto like in person?

“He was a replica of Chinua, except that his father gave him some inches in height. One may say that Chinua may later look as huge as his father,” she said, referring to her first son, Chinualum, named after the Things Fall Apart author.

Paul Onyemechi Onovoh, who met Ezenwa-Ohaeto for the first time in 1990 at the Eagle on Iroko International Symposium celebrating Chinua Achebe’s sixtieth birthday, remembers him as “an easy-going, unassuming, polite, friendly and energetic man with jet-black hair.”

Born on March 31, 1958, Ezenwa-Ohaeto had his primary education at Ife in Imo state and had his secondary school experience at St Augustine, Nkwerre, also in Imo. Originally from Owerri-Nkworji, he was the third child and first son of Venerable Michael Ogbonnaya Ohaeto and Rebecca N. Ohaeto.

“He started with drawings,” she told me after I asked if Ezenwa-Ohaeto was arty as a child. “He was a fine artist and he was good at it, but he started writing when he was in secondary school.”

She met Ezenwa-Ohaeto at the then Anambra state College of Education, Awka. “Ezenwa was my teacher. We were people that got to know themselves and had common interests. It was not the kind of thing that happens in schools today where some lecturers take advantage of some students, it wasn’t that kind of thing. It was something that was formal and once agreed, he didn’t waste time to see my parents. He was a young man, promising, I like good things; he was my kind of man.”

She would accompany him to Nsukka to visit Chinua Achebe at Nsukka when he was collecting data for the biography. “Chinua Achebe was his mentor. Chinua Achebe believed in him, because he was his teacher too, and he knew about his (Ezenwa-Ohaeto’s) writing prowess when he was an undergraduate at Nsukka.” She disclosed that Ezenwa-Ohaeto was actually running his post-graduate program when he approached Chinua Achebe on the subject of the biography. “He was following Chinua Achebe about, even to his village, to his uncles. He gathered firsthand information about Chinua. By the time he permitted him to work on the biography, Ezenwa had gone far in gathering data. And you know Chinua Achebe is not somebody who could easily grant permission without knowing that, yes, this person can do it. And he was not disappointed when the book came out.”

How did she feel the first time she met Chinua Achebe through her husband-to-be?

“I had read Things Fall Apart, No Longer at Ease, Arrow of God, and when I saw him I was like, wow. He wasn’t as tall as Okonkwo and I used to admire the story of Things Fall Apart when I was in secondary school. When I first saw him, I was surprised. The humility I observed, the gentleness of the voice, he was sort of picking his words; I was expecting somebody that spoke like Okonkwo. His creation, Okonkwo, was far from him, in physique and character.”

Soon after the first draft of the biography was done and at the time she and Ezenwa-Ohaeto had married, he had a crushing experience, an event with the potential of murdering his lofty goal. The biographical manuscript got lost.

“He parked his car somewhere at Eke Awka and went to buy something. When he came back, his car had been burgled. You know Mercedes was an exotic car at that time, so these people must have thought that there was a lot of money in the car. The manuscript was in a travelling bag, so they carried the bag.” She remembers him returning home that day and informing her of what had happened. “You could tell that he had lost half of him.”

“Because I felt that these people would be disappointed that it is only a manuscript in the bag and not money,” she went with one of her friends into the dumps in Awka hinterland, scavenging dirt, hunting for the bag, praying that the thieves had disposed of it. Her hopes would be dashed. “Unfortunately we could not find it.”

But Ezenwa-Ohaeto’s resolve to actualize the project was not shattered, it also helped that he was aware of the caliber of person he was writing on “and that the person knew that no obstacle would stop him.” Armed with the recorded tapes of the interviews and other data he had gathered, “He started all over again.”

He was a man on a mission, a commitment to document and dispassionately present the lives of Nigerian writers and critics active in his time and those before him. “I know that the person I lived with had this urge, this uncontrollable urge, to pursue writers; I remember following him to visit John Munonye for interview after reading his book, The Only Son,” she said. “It was all about passion.”

Faithful to the title of his debut collection of poetry, Songs of a Traveller, published in 1986, Ezenwa-Ohaeto was a traveller who had taught at the Kano Campus of Ahmadu Bello University, Alvan Ikoku Institute for Education, Owerri, the Universities of Mainz and Bayreuth, both in Germany. He was once at Bellagio, Italy, on the Rockefeller Residency, where a substantial part of his final collection of poems, The Chants of a Minstrel, was “not only completed but refined.” Did the fact that he enjoyed travelling ever cause friction in their marriage?

“I knew he was a traveller before accepting him,” Ngozi said. “I joined him in travelling at a point. He would travel and come back, never stayed away for too long.”

For a man with seemingly multiple literary interests, what could be the monumental ideal propelling him?

“He was a social crusader,” Ngozi said. “One of the things he was after was colonial influence, to help create awareness of who we are. If you look at his poetry, he was into satire. He was into criticizing the wrongs in society, especially during the military era.”

Ezenwa-Ohaeto appeared to be at the zenith of his creative abilities during the years the military ran the affairs of Nigeria, for it was in those decades that he published I Wan Bi President (1988) and Bullets for Buntings (1989) which could pass for subtle responses to the repressive General Ibrahim Babangida regime. Then came The Voice of the Night Masquerade (1996) which won the ANA/Cadbury prize, If To Say I be Soja and Pieces of Madness. “He was into corrective writing,” Ngozi pointed out.

Two years before his demise, he had published Winging Words: Interviews with Nigerian Writers and Critics. In the 172-paged book which embodied 21 interviews “conducted in the midst of harsh economic conditions” over a period of 15 years, Ezenwa-Ohaeto captured “for posterity some ideas and thoughts that would have been lost forever.”

In 2005, he co-won the Nigeria Prize for Literature prize alongside the poet, Gabriel Okara. He had also commenced work on the biography of the Nobel laureate, Wole Soyinka. That same year, shortly after arriving at Cambridge, United Kingdom, he got knocked down by liver cancer. When Dr. Derek R. Peterson, Director of the African Studies Centre and Fellow of Selwyn College, Cambridge University, came to see him, “he was in good spirits, eager to talk, and very firm about his desire to return to Nigeria.” He would pass on the next day at Addenbrookes hospital, leaving behind a young wife and four kids.

J.O.J Nwachukwu-Agbada described Ezenwa-Ohaeto as the poet who used “the humour in njakiri to smooth his way through. Although he was regularly concerned with the fate of fellow nationals, he did so light-heartedly, combining the use of airy Igbo iconic figures with mediated English and pidgin variety. Ezenwa-Ohaeto left behind an original, captivating and enchanting poetic tradition.”

When I reached out to him for an interview, Ezenwa-Ohaeto’s first son, Chinualum, admitted that he has very blurred memories of his father. Himself, a critically acclaimed poet, Chinualum has often been compared to his father; Mrs. Ezenwa-Ohaeto thinks this is an unfair assessment as both father and son were bred under different backgrounds, committed to different artistic objectives. “I think Chinua is doing well, I am well impressed by his work so far. He needs to work hard since he has decided to toe his father’s line, but I don’t want to accept he is working to fill his father’s shoes. His father’s name would be a challenge to him and a blessing to him; that the name is there doesn’t mean he is that name.”

She added, “I remember the day Ezenwa’s body was brought to this university’s auditorium, the then Professor Ilochi Okafor pointedly told me that Ezenwa had left a very big shoe, that I need to wake up and meet up with that size. I told myself that Ezenwa wore his shoe, so I’m going to wear mine.”

To sustain the memory and appreciation of the work of her husband, Mrs. Ezenwa-Ohaeto founded the Ezenwa-Ohaeto Resource Centre, which almost functions as a public library in Awka, Anambra state. The board of directors and patrons of the establishment include Professors Chukwuemeka Ike, Ernest Emenyonu and Charles Nnolim, Chinyere Okunna and Odia Ofeimun. She also occasionally hosts colloquiums, seminars and other literary events where writers and scholars all over the country and beyond are invited to discuss on gender, religion, arts, amongst others.

“When you see someone who is so much dedicated to the work he’s doing and you see a lot of work facing him, then suddenly, he’s no more, naturally you’d be touched. There’s so much to be done about him, I’ve not even started,” Mrs Ezenwa-Ohaeto said. “I am doing what I should do.”

What eventually became of the Wole Soyinka biography her husband was working on?

“The work is going on right now. I’m on it. A bit of it was published two Sundays ago in the newspaper. Very soon the work will be out. We’re also working on Chukwuemeka Ike’s biography, too. Our plan is that once this one is done, we’d commence on Ike’s story. The kind of material he gathered on Soyinka almost filled half of my room; to put such data together is not an easy task.

“He died the very year I got appointment letter to this school; it was at the beginning of my career that it happened. I lost a lot by his death, but I picked up. It was not easy, it was shattering, it was heartbreaking, physically, mentally, emotionally, but I got my broken parts and moved on. And thank God for the kind of children I am blessed with, because if I hadn’t had supportive and understanding children, I don’t know. I thank God for them, starting from Chinua down to Uche; they’re my source of strength. Since 2005 that my husband died, my blessings have been uncountable.” ✚

Eloka is an Editor at the Question Marker.